Having been born and raised in the coastal regions of the Philippines, I had the privilege of experiencing the oceans of the Coral Triangle from an early age. At the age of 10, I was introduced to scuba diving, which sparked a significant interest in marine biodiversity. Over the past seven years, my family and I have dived all over the Philippines. I have come to deeply appreciate coral reefs as a vital component of marine ecosystems. Diving fuels my passion for biology and reinforces my understanding that our efforts to preserve the ocean must involve recognizing humanity’s reliance on and responsibility for this magnificent ecosystem.

The ocean, covering over 70 percent of the Earth’s surface, acts as the planet’s life-support system, regulating climate, absorbing carbon dioxide, and generating more than half of the oxygen essential for life.

Despite occupying less than 0.1 percent of the ocean floor, coral reefs play a disproportionately large role in marine ecosystems and human livelihoods. However, due to human activities over the last decades, coral reefs face threats to their continued existence.

Coral reefs are essential to the survival of approximately 25 percent of all marine species, supporting complex food webs and providing a basis for local tourism industries. Yet, it is estimated that nearly 50 percent of the world’s coral reefs have been lost or severely degraded. The primary threats include overfishing, pollution, unsustainable coastal development, and, more prominently, climate change.

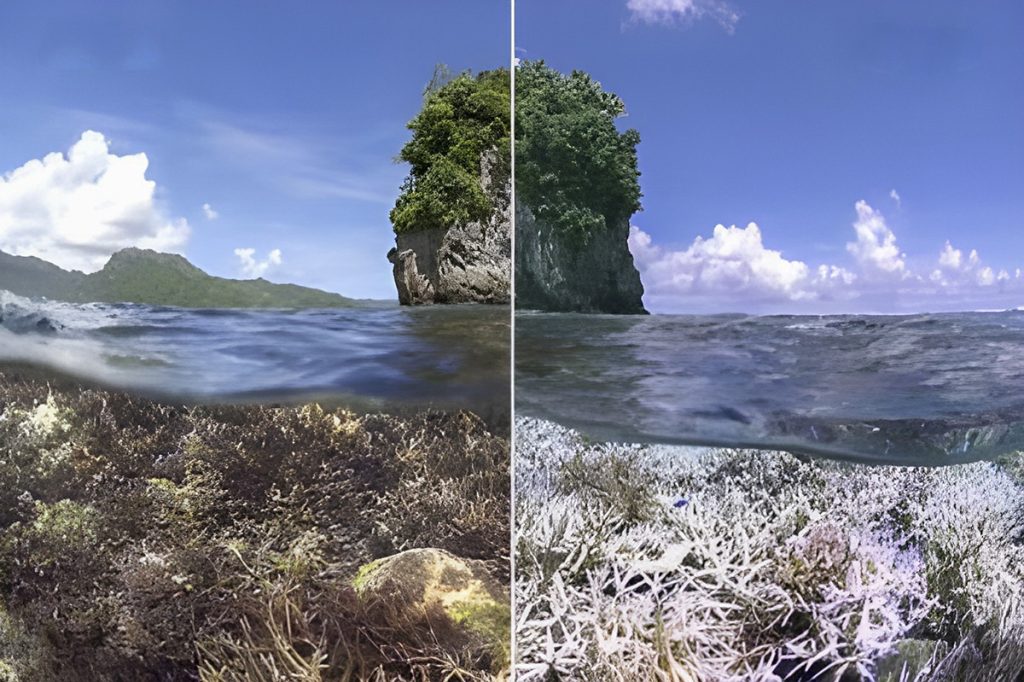

Climate change is causing rising sea surface temperatures and ocean acidification, both of which are harmful to coral health. Coral bleaching, where corals expel their symbiotic algae due to thermal stress, has become increasingly severe. The 1998 global coral bleaching event, caused by a strong El Niño, resulted in the loss of approximately 16 percent of the world’s coral reefs in just one year. According to climate models, 70-90 percent of coral reefs could disappear by mid-century if global temperatures continue to rise.

Additionally, ocean acidification—driven by approximately 30 percent of human-made carbon dioxide emissions—has caused a measurable decrease in seawater pH, from around 8.2 to 8.1 since the Industrial Revolution. While this change may seem marginal, it significantly affects the ability of corals and other marine organisms to form calcium carbonate skeletons, weakening the structural integrity of reef ecosystems. Projections suggest that ocean pH could drop an additional 0.3 to 0.4 units by 2100, further threatening coral existence.

In response to these challenges, coral restoration is a significant intervention to mitigate reef degradation. During my field experience shadowing Dr. Peter Harrison’s team in Zambales, I observed the complexities of coral restoration through sexual reproduction. This method combines the male and female gametes (eggs and sperm) of corals to achieve genetic diversity and produce new corals.

Coral spawning is a critical event in the life cycle of many coral species, offering an opportunity for genetic recombination, thereby increasing adaptive potential in changing environments. Dr. Harrison’s team followed a method he developed to prepare for coral spawning. They inspected coral colonies over the days leading up to the event to gauge their readiness for gamete release. Cone-shaped nets with attached containers were placed over the corals to collect all coral gametes. These were then cultivated in controlled lab environments to maximize larval survival.

However, the restoration process is challenging. During my time in Zambales, a severe thunderstorm hit just as preparations were being made for coral spawning. The team had to abandon the site early to escape the storm, which disrupted the process and illustrated the fragility of restoration efforts. Natural stressors like storms can destroy coral breeding grounds and prevent coral larvae from finding suitable locations to settle and grow, thus affecting reef formation and expansion.

Coral rescue base

Inspired by the insight gained in Zambales, I am now involved in a coral restoration initiative at Coral Cliff in Calape, Bohol. In collaboration with H Resort, local non-government organizations (NGOs), and government bodies, this project aims for coral restoration and community-based marine conservation. Coral reefs in this region are under significant pressure from climate change and local human activities, threatening biodiversity and the livelihoods of local fishing communities.

The reefs at Coral Cliff, in particular, face the problem of earthquakes. Bohol, located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, is susceptible to seismic activity. Earthquakes can cause physical damage to coral reefs by shifting underwater structures and dislodging coral colonies. These compounded threats—both natural and human-made—make the preservation of coral reefs here an urgent priority.

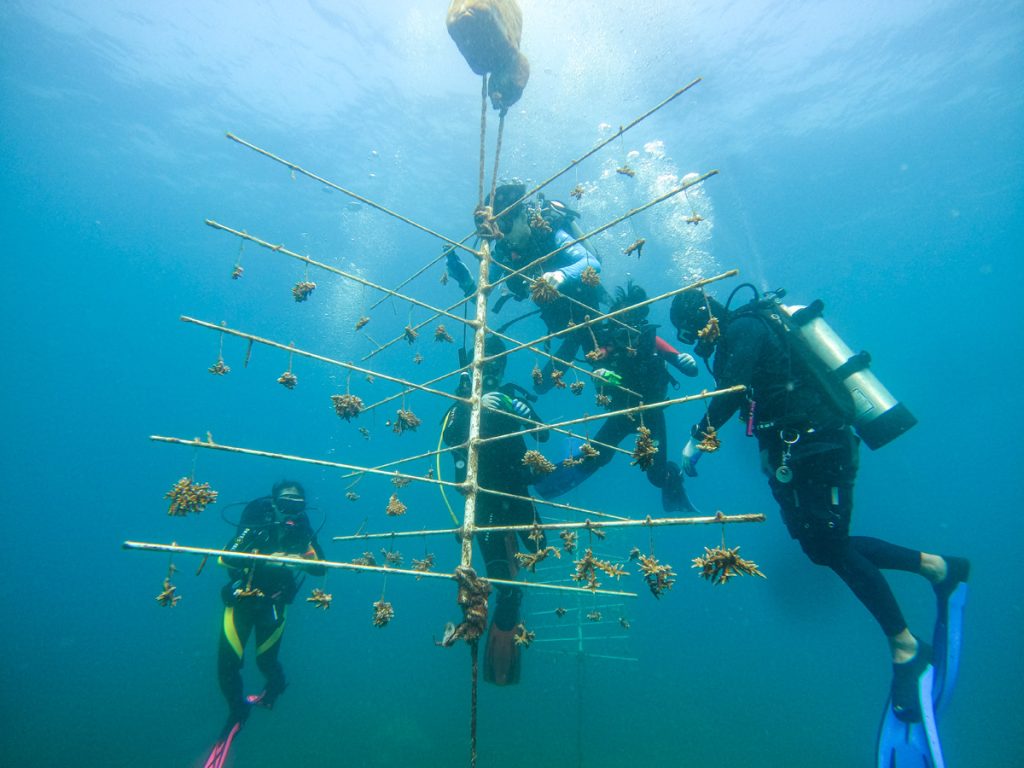

While Dr. Harrison’s team in Zambales focused on sexual reproduction to increase genetic diversity, the restoration efforts at Coral Cliff will primarily employ asexual fragmentation techniques. Asexual reproduction, while not enhancing genetic diversity, allows for the rapid propagation of coral fragments that are later transplanted onto degraded reef areas. This method enables large-scale restoration in a relatively short time, deeming it an effective immediate strategy for addressing coral loss.

The Coral Cliff initiative will also engage local volunteers, students, and environmental advocates in hands-on coral restoration activities. Participants will be trained in nursery maintenance, coral fragment cleaning, and reef monitoring. Involving the community is critical to the long-term success of the project, as it will foster a better sense of environmental responsibility.

The rapid degradation of coral reefs worldwide is a stark reminder of the broader environmental crisis driven by human activity. They may become functionally extinct within the next few decades, leading to catastrophic consequences for marine ecosystems and the millions of people who rely on them for food, income, and coastal protection without intervention. Though despite this, studies show that coral reefs have remarkable recovery potential if the primary drivers of their degradation—climate change, overfishing, and pollution —are addressed.

The future of coral reefs requires a coordinated, global response that includes local community involvement, policy changes, and public awareness. Governments must enact stronger environmental regulations, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote sustainable coastal development. Simultaneously, individuals and communities must engage in conservation initiatives by getting involved in restoration projects or adopting more sustainable lifestyle choices.

Local community engagement

At Coral Cliff, our focus is on working with the local government to engage local communities in marine conservation while implementing practical restoration techniques. By empowering local communities to take responsibility for the health of their local ecosystems, restoration efforts like those at Coral Cliff offer a scalable solution to help preserve such ecosystems for future generations.

Coral reefs are among the most critical ecosystems on the planet, supporting marine biodiversity and human economies. Collectively, the integration of scientific research, community engagement, and targeted restoration efforts can slow the decline of coral reefs and promote recovery. The Coral Cliff restoration project in Bohol represents a small but significant step toward preserving these vital ecosystems. Future directions for coral restoration could involve further research in marine biology, ecology, and climate science research to develop innovative techniques for enhancing coral resilience. Additionally, marine projects such as mangrove restoration and seagrass conservation can complement coral restoration by improving overall coastal ecosystem robustness.

Ultimately, only through collective global action and the integration of diverse scientific disciplines can we preserve coral reefs for future generations.

“Collective global action” means nothing without the masses. In these moments, I encourage you to ask yourself: If not me, who? If not now, when? Bad things arise from good people doing nothing.