Asian Dragon talked to Mayor Duterte back in July when he was still reluctant to run for the presidency. Published first in Asian Dragon Magazine July-August 2015, the story of Mayor Duterte reveals the real man behind his violent demeanor and his plans on how to run and save this country.

To run or not to run? That is the question. The signs are everywhere that Mayor Rodrigo Duterte is going to. He has been consistently quoted in various interviews saying that he isn’t running. “I don’t want to run,” he says. “Why? Because I’m old already and don’t have the money. And when I close my eyes, I see no difference between being a Mayor Duterte and a President Duterte; it’s all the same to me. I’ve been telling people that I have accumulated enough accolades to last a lifetime and I don’t need to add the presidency.” He also considers how the presidency is perceived, with people easily accusing one of corruption as a result of the negative image brought about by botched government deals like the MRT, for instance. “I don’t need it,” he says emphatically.

So why won’t people leave him alone? Why do they keep convincing him to run, even financing his political ads despite his reluctance?

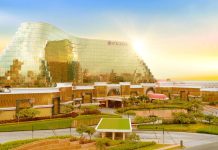

For one, he has a great track record. Ask any man on the street in Davao, and he will tell you that Mayor Duterte was the only one who brought peace and order as well as prosperity to their city. On June 13, 2015, the global database Numbeo released its list of top 10 safest cities in Southeast Asia and ranked Davao second, with an 18.65 crime index after Singapore’s 16.76. Not bad at all. They even have a 9-11 call center patterned after that of the US, which has helped not only solve but also prevent a lot of crimes. They have cameras in all major thoroughfares with 24/7 surveillance, so police action is almost instantaneous. Even if the riding public find the speed limit of 40 kph a bit conservative, traffic obedience is amazing because everyone is aware of the pitfalls of wanton disregard for traffic rules. And because of these, there is investor confidence. Hotels have mushroomed; with five-star hotels like Ayala’s Seda, in addition to Marco Polo, they now have enough rooms to make it a favorite regional and even national convention hub.

Duterte says that after 22 years as Davao Mayor, it’s only now that he has gained national recognition. “Actually, I have never gotten involved in national issues in the past. I’ve been a very private person ever since.” Pivotal was the visit of former governor Lito Osmeña, former senator Aquilino Pimentel, Jr., and Reuben Canoy, owner of Radio Mindanao Network, the original proponents of federalism. “Several times they asked me to again carry the torch of federalism,” he says, after the original group’s efforts failed to come to fruition.

“I agreed to advocate federalism, considering the red lights in Mindanao. If the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) is not passed, there is that threat of war by Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Chair Murad Ebrahim. President Aquino and Sec. Teresita Deles, presidential adviser on the peace process, have validated these threats of Murad and have painted a very grim picture of what will happen if there is no BBL,” says Duterte.

Meanwhile, Misuari has emerged and called for the fulfillment of the Tripoli Agreement, so the plot thickens. “I am quite passionate about the situation because if war breaks out, you know where the battleground will be—Mindanao and Davao City, in particular,” he says. “We in Mindanao will suffer. I wish to remind everybody of the past, the bombing of the cathedral, though it didn’t happen during my time. Two bombs went off after Holy Week, and there was a church bombing during a midnight mass during my time. A month after, it was the Davao International Airport, followed by the port and bus terminal. All in all, about 117 people were killed. Duterte is for the passing of the BBL; however, if it doesn’t pass the test of constitutionality before the Supreme Court, then we must accept it.”

So what kind of federalism model does Duterte actually have in mind? “There are plenty of models to choose from. It could be the US Electoral College, or like in France, where only the president is nationally elected and everyone else represents a local or limited territory. Indonesia is a federal parliament, Australia and New Zealand too. Singapore, Japan, and Malaysia are likewise federal parliaments,” he explains, but he seems more partial to the Singapore or Malaysian model.

The transition, he says, will have to go through a process, either a constitutional convention or congress converting itself into a constituent body that can amend the constitution by itself. The better option, he believes, would be a constitutional convention.

So what can we expect from a Duterte presidency? Will he be able to do for the whole Philippines what he did for Davao?

First and foremost is bringing back law and order. “You know, the doubt of the moment is really the criminality issue, and this is associated with drugs. Drug activity must stop. If you want an example of what can happen to a country flooded with drugs, take a look at Mexico. I would challenge everybody in this room, ask a mayor of any city frankly what is the serious problem of the city, and he would answer you, drugs. Imagine a nine-month-old baby raped, a monstrous act that can only be done by someone under the influence of drugs. That’s everyone’s number one problem. Second is corruption. People are looking for somebody to stop corruption.”

He has a practical solution for the corruption problem. After all, he does have Chinese blood (his maternal grandfather is Cantonese, with the surname Lam).

Duterte says he would revise and simplify our taxation laws. “If you are earning P24,000 and below, no more income tax—the rest will be a gross tax on everything. Show your expenses, and there is a tax schedule. It’s been done in Singapore and Malaysia. You could also privatize the Bureau of Internal Revenue, go to any BIR office and ask for a list of what needs to be submitted. Assure business people of no extortion from anybody, whether police, BIR, or Customs. Allow them to do business, and they will be happy,” he says.

Duterte believes in being pro-business. “I would like to see investments coming in. Then, we have to revise our laws and regulations to make it easier for them to deal with government. For example, in a department or authorizing body, I would limit the period where they can sit down on an application. If you do not have the workers, tell me; I will ease restrictions. I will make it easy for business to go direct to Customs. If you are not satisfied, you are welcome any time to tell me your problems.”

For manufacturing, “We still need more investments, so I will make it easy for them to get the raw materials. Then, infrastructure must be there. The Philippines is still fundamentally an agricultural country, so you have to encourage and prepare our farmers for this. No more land reform, just give farmers assistance like farm inputs, fertilizers, seedlings, and make sure that their products get sold at competitive prices.”

Duterte thinks that the less intervention there is in business by government, the better. “The 148 signatures required to complete a contract and establish a business here in the Philippines is stupid,” he says. The Department of Trade and Industry must see to it that everything is in order along the lines of documentation, while the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) will have only 72 hours if they have to plan inspections.

Just one caveat for business people, though. “As a businessman, give me the assurance that you are telling the truth.” If not, his figurative (and, we hope, not literal) warning is, “I will load you into a container and throw you into Manila Bay—and if you do drugs, you’re dead!”

Duterte also believes in population control, so that families can provide quality of life to their children. Health centers give out pills and charge a minimal fee of P5,000 for tubal ligation as a method of female sterilization. Local government and police enforcers also take a practical stance on prostitution. Commercial sex workers have to undergo strict health screening and are licensed, pretty much like in other Asean countries. In Davao, it is a legal profession, and thus, they are neither harassed nor taken advantage of by law enforcers.

But then, that is all a big “if”—if he decides to run for the presidency.

“A lot of my friends have been spending already, and I said that the thought of being a president has not sunk in yet. The problem with being president is, whether you do right or wrong, by default it’s wrong. As a mayor, I work 30 hours a day, not 24 hours. If you are president, you work 50 hours a day. I wonder why so many people want the presidency?” he asks.

Duterte’s equally tough daughter, former Davao Mayor Inday Sara, asked one of her father’s close friends, businessman Sammy Uy, to dissuade her father from running. “Kawawa s’ya,” Inday Sara says. “He already has everything, why run?”

The only good Duterte sees in this situation is, it could give him commanding leadership not only in Mindanao, but also in the Visayas—and that in itself is a valuable source of power.

At the end of the day, Duterte believes that whether or not one becomes president really depends on one’s destiny. So we shall wait and see if being president is truly in the man’s stars.

Rodrigo “Digong” or “Rody” Duterte is the second of five children of Vicente Duterte and Soledad R. Duterte. His father was from Cebu, while his mother was originally from Mindanao; they migrated to Davao from Cebu. At that time, almost all migrants to Davao were poor. “I’m the son of a poor man. It was a long and winding road of sacrifice. I know the meaning of hardship. Maybe that’s why I am close to the masses.”

His father was a lawyer who became the first Mayor of Davao. Eventually he became Governor, and his last stint was as a cabinet secretary for general services in charge of printing and supplies during the Marcos regime. He resigned because he couldn’t stand the pressure of the position, went back to Davao, and stayed there until his passing. Duterte describes his father as a kind man, not controversial. His mother Soledad was a teacher.

Duterte went to public school for his elementary and high school education, and moved to Lyceum in Manila for his undergraduate course, AB Political Science and International Studies. He entered San Beda law school in 1972, when martial law was declared. Though he was shy in his younger years, he was never one to put up with bullying. In law school, he experienced the bigotry of Manilans.

Duterte recalls a student shouting to his colleagues, “’Adre! Nagkakalat ang mundo ng mga Bisaya. Nandito, dumating na.” “There were only three of us Visayans there at that time,” he recalls. Another time, while he was saying goodbye to a classmate in the covered court of San Beda, a passer-by loudly announced, “Aba! May kotse pala itong mga Bisaya.” “He didn’t know I heard and saw what he did, so I got out of the car and taught him a lesson,” Duterte says.

Then, on their last term before graduation, while waiting in the corridor for a class, a bully took a fancy to some students and started flicking the noses of everyone. “When he got to me, I told him, ’Adre, don’t do that to me or you’re going to get it.’ He said, ‘Oh, I don’t believe you!’ So I did what I had to do.”

He became a lawyer and worked for Davao Timber Corporation as their house counsel for about six months. When there was an opening in the Prosecutor’s Office in Davao, he took a chance and became a prosecutor for 10 years, specializing in trial law, from criminal to civil cases. “I’m not bright, but I was very observant and willing to learn. I’d stay on after my hearings and sit in the hearings of other cases to listen and learn from the best and smartest lawyers. Eventually, I developed my own style.”

So when Duterte challenged Justice Leila de Lima to court to put her on the witness stand so he can cross-examine her, he knows he will be in his element as a prosecutor.

His mother Soledad was a member of the opposition during the Marcos Regime. When Cory Aquino won after the People Power Revolution in 1986, she was offered a vice mayoral post, which she politely declined. Duterte took her place; the mayor then was Safiro Respicio.

Eventually, Duterte had a falling out with Respicio and decided to run against him. Duterte was the only one who had the guts to go against Respicio; he figured he didn’t have anything to lose. In 1988, at age 43, Duterte became mayor of Davao City and won on the platform of peace and order. In a city that was like the wild, wild west, with killings in the streets, rampant kidnapping, and a strong New People’s Army, that was a tall order, especially for a newbie in politics. In his inaugural speech, he warned bad elements to get out of Davao. Given the gravity of the situation, he succeeded in bringing order and sanity to Davao only on his second term.

In the last 27 years, from 1988 to 2015, Duterte has never lost an election. He also assumed different posts, including vice mayor and congressman, between terms. He prefers to be in local government, though, because “you can execute your plans and see them bear fruit. It keeps you busy the whole day long, thinking of ways to improve governance.”

As a local government official, he isn’t your typical politician. He lives in a simple medium-sized abode in a middle-class subdivision. He has a taxi that helped augment his income while he was vice mayor. He doesn’t like putting his picture on the banners of his various projects. Epal, which now refers to a politician’s shameless self-promotion, is something you won’t see in Davao. “It’s important to have a sense of delicadeza,” he says.

He is also a firm believer in walking the talk. When he imposed the maximum speed limit policy in Davao, his daughter Inday Sara was one of the first to get caught. “There are no exceptions. There’s no drama there. We are a family with no pretensions.”

As the strong man of Davao, with close to three decades in power, one wonders how he managed to stay grounded. Duterte says it’s because of his father. When they were young, each sibling had his own dreams and ambitions. One wanted to be a doctor, while Duterte wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father. “My father would remind us of our humble beginnings. He told us, you should bear in mind, it is not easy to be a politician. To win, you have to earn the trust and love of the people. Once you are in power, be humble and stay only until you are in a position to help. Sometimes, you need to be humble to the point of losing your dignity.” And that is exactly how Rodrigo Duterte has lived his life as a politician.

IN HIS WORDS: Mayor Duterte answers the hard questions

AD: How would you reconcile being a lawyer and sometimes doing things that may be perceived to be against the law?

Duterte: I promised to curb criminality in Davao and restore order and sanity. That is my role. In my inaugural speech, I did warn criminals to stay out of Davao because if you stay here you may die. I never said, police will kill so and so…

AD: Do you have a lot of cases filed against you?

Duterte: None at the moment, but before, somebody put cemented flooring in the canals, which prevented us from cleaning them. I had it demolished, and the person filed a case against me. The case reached the Supreme Court and the complainant lost. In Davao City, you have to comply with the rules of the city. No one is exempted.

AD: There are some people who say that you are at times brazen and lacking in diplomacy, as evidenced by your use of expletives. If you become president, you would have to use more diplomatic language—are you ready for this?

Duterte: If I’m an ambassador, then maybe I will have to keep silent. (Chuckles) But if it’s just in my office, maybe you can expect that from me every day. But I don’t give a sh-t. I won’t mend my ways. I can’t change at 70.

AD: As president, you would have to reconcile and unite the country, like the MILF, MNLF. etc. It is said that both your son Paolo and daughter Inday Sara want to run as mayor in the next elections. How would you manage that situation, because if you can’t unite your family, wouldn’t it be more difficult to unite our country?

Duterte: No, we’re united. I like Inday because she is a lawyer, she’s also tough.

AD: Are you married?

Duterte: Yes, but divorced.

AD: You succeeded in making Davao what it is today. Don’t you want to see if you can make things work on a bigger scale?

Duterte: The problem is, nagre-reset ang mind ko; my mind is telling me, “Rodrigo, why are you looking for trouble?”

AD: What will happen to our country if only those who are corrupt will become president?

Duterte: Right now, it’s between two persons, Grace Poe and Jejomar Binay. Binay has the edge. Whatever is the outcome, though, I believe, is destiny.

Contact Asian Dragon Magazine for orders or purchase the issue from the Asian Dragon Magazine App, free to download on Google Play Store, iTunes, and Amazon.

[Photographs: Edwin Tuyay]