I first interviewed chef-restaurateur Gene Gonzalez in 1986 for his vintage car collection and his passion for cooking. He debuted just a year ahead of Margarita Forés in the culinary scene. Both showed the younger generation the possibilities of a full-time culinary career.

Without any formal training, the enterprising Gonzalez was one of the trendsetters, along with journalist-turned-restaurateur Lorenzo Cruz, who introduced fine dining in turn-of-the-century settings. Gonzalez’s Café Ysabel along P. Guevarra, San Juan was set in an ancestral home built in 1912. It was known as a date place, as it was furnished with high-backed seaters and cozy corners. He served classic continental and heirloom recipes.

A lot of things had transpired since we last saw him three decades ago. Gonzalez had nearly closed his restaurant twice—once during the height of the brownouts during President Cory Aquino’s term, and again during the Asian Crisis in 1998. A few years ago, he battled prostate cancer for two years and is now in remission.

Still, Gonzalez has remained productive. He has been working as a consultant for small hotels and resorts, creating manuals for kitchens. He designed a successful system for the Vikings Restaurant chain and for Max Restaurant’s rebranding as a Filipino family restaurant. He developed the logistics for keeping the freshness of the recipes of the late matriarch Ruby Trota, for the chain’s 80 outlets.

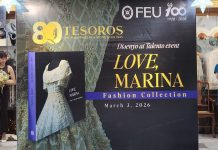

Gonzalez has written over 30 books, and some have won international World Gourmand Awards. Philippine Breads was his research on traditional breads that were disappearing as Filipinos favored foreign franchises. Philippine Confections is his recipe book on Filipinized Western sweets, such as langka marshmallow and buko pandan macarons. Among his bestsellers is Pinoy Classic Cuisine, a series on home cooking recipes and cocktails, which won the Manila Critics Circle Awards.

As the restaurant scene became more competitive with the rise of malls, Gonzalez opened the Center for Asian Culinary Studies, of which he is the president and head instructor. His eldest, Gino, is his right hand, while his daughter Giannina is a food stylist and owner of a restaurant for pets and their owners called Whole Pet Kitchen and Bark-ery. Gonzalez and his daughter collaborate to offer “dog-gustacions.”

On planning the menu, he thinks of his guests first. “It’s not what I want to serve, but who is going to eat and what can I serve for that person. Chefs can say, ‘I can serve this without being considerate of others who will participate in his work.’ The chef should participate in what others will enjoy rather than present something egotistical—‘I can cook this.’ You might impress people, but will they like the food? Will people eat or will they just taste? They may get impressed, but the most important thing is that they should enjoy eating,” explained Gonzalez.

Breaded lamb with Béarnaise sauce and wild fig confit; ‘Lengua’ on a bed of mofongo, topped with pork cracklings

Gonzalez holds either tasting events or regular Sunday dinners, which started out with his family—his siblings, his children, and other relatives. After his bout with cancer, he expanded the guest list to include friends from childhood days, karate groups, and fashion industry insiders.

There are wine pairing dinners for collectors and tasting meals for his new recipes.

Sunday dinners are always a surprise. He wants the guests to anticipate the meals, and not predict what he’s going to serve.

“We revolve around certain themes. I came from Hanoi, so we will do a workshop where we can file our recipes and serve. Northern cuisine is subtle and powerful, focusing on natural flavors. We will serve fish fillet coated in turmeric and fresh herbs with shrimp paste and spring rolls,” he said.

When the guests hanker for traditional meals, Gonzalez reverts to heirloom recipes from Pampanga. Back in the ’80s, the country became aware of Sulipeño cuisine, a melding of Malay, Basque, and French influences from his hometown in Apalit. The town was a port where there were a lot of cultural and culinary exchanges. “We serve an elegant sinigang that is slightly soured using river prawns; canalones with ground liver paté, brain, cheese and béchamel sauce, and braised turkey with olives and capers and doused in wine. The lengua is on a bed of mofongo, mashed fried plantains with butter and pork cracklings, and the classic paella,” he said.

‘Tocino del cielo’; ‘Ensaymada’ from a 200-year-old recipe

He also shared tocino del cielo, a 200-year-old recipe made of sugar, butter, and translucent custard. The ensaymada, another heirloom recipe, uses more egg yolks and requires three risings for an ethereal texture, unlike today’s pastry, which only undergoes one or two risings.

Over lunch, he served coral grouper with a salsa of mango, pomelo, macopa, and passion fruit and an overload of saba fries instead of potatoes. The meat dish was breaded lamb cutlets coated in Parmesan cheese, accompanied by béarnaise sauce and wild fig confit. The figs were harvested from the garden. The vegan meal consisted of mushrooms with herbs, grilled gluten cutlets that looked like pork, and turmeric rice. We finished with a dark chocolate cake and fig leaf tea.

Photographs by Paul San Juan