Upon first meeting Lindslee, one could have been forgiven for expecting a raging, defiant iconoclast behind the works of modern deconstruction that have recently been mounted in Manila’s modern galleries. The reviews that have praised his pieces write about the intensity that belies the motion and color in his paintings. Some of them go to great lengths to analyze how he literally tears down and rips apart the elements of traditional art in order to come up with a sculpture or a carving that evokes rebellion or a blazing sense of freedom. But the artist and young father appears to be an oasis of calm.

“If something bad happens to you, it’s already destroyed some things in your life,” the man born as Lindsley James Lee says, waxing philosophical. “If you continue to feel bad about it, it’s a negative event. But you can think more positive, like making lemonade if life throws you a lemon. You can’t believe that just because you’re in a bad situation, you cannot make it better.”

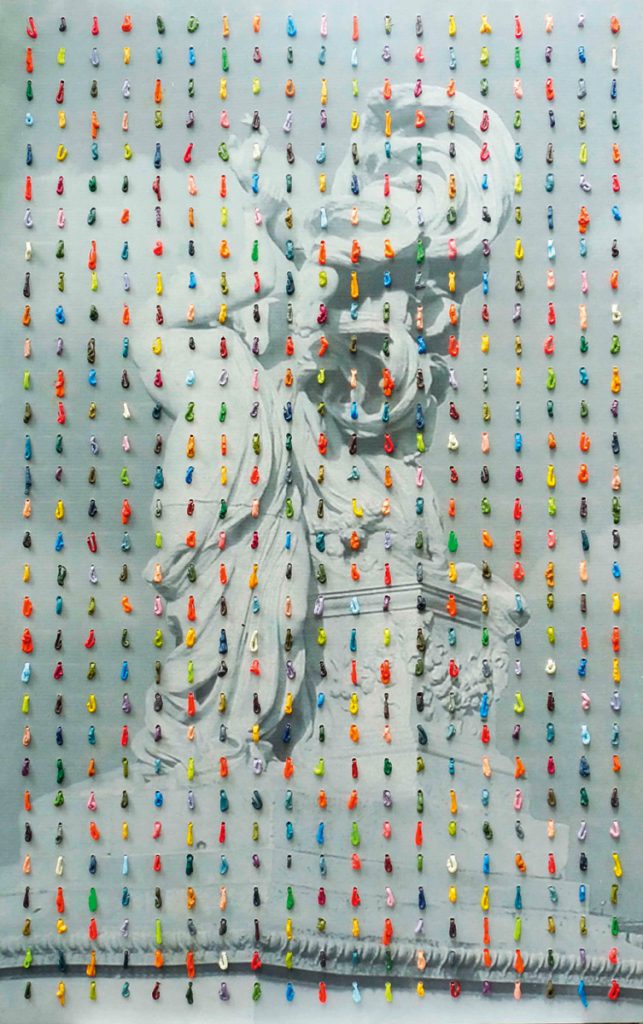

A look at some of his works at the Galleria Duemila can be interpreted as an examination of the worst side of Philippine society. Mixing the classicism of Greek sculpture and homegrown rustic culture, his representation of Blind Justice uses the Pinoy sabong (cockfight) as its standard of measurement, evoking various images of corruption and bureaucracy. Another piece that shows a small portrait surrounded by a much darker frame can be interpreted as an indictment of the narcissistic selfie phenomenon.

Lindslee points at another piece which he calls Consumption. “You see this big guy holding two chickens,” he says, “It’s not just about eating, but how we consume everything, and abuse other things in the process. It’s about our internal struggle as humans.”

But he does not attach any elements of darkness to his current pieces, choosing instead to see the more humorous part of life that is reflected in them. “What’s important is that people can relate to them, and my works provoke a lot of discussion,” he says.

He has always loved drawing as a little boy, sketching pictures on walls and doors. Winning an art contest in high school confirmed that he did have the gift, and made him realize what would soon be his lifelong calling. Although he did his fair share helping out in the family merchandising store in Bacolod, there was no pressure from his Chinese parents to assume their roles; that honor had been left to his older brother, he laughingly acknowledges. That left him free to take up Fine Arts at the University of Santo Tomas. A few years later, he would study art courses in New York, and complete a two-month artist’s residency in Japan.

“You just can’t wait for the inspiration to come to you,” he says. “You need to explore, travel, and feel the reality around you. I watch people and try to think what they’re thinking and feel what they’re feeling.”

One way he recharges is to literally observe the crowds in busy marketplaces like Cubao, Divisoria, and Escolta. Then there are times he just wants to chill out by going back to nature. A Tanay property has become his ideal camping ground. “There’s no electricity, no cellphone signal, and you have to find your own water. You use candles and gas lamps for light. I stay in that place for two nights.”

And when the Muse does come, sometimes it extols him to break boundaries and push the envelope, leading to the labels of deconstructionism. “My mixture of Greek art and Filipino culture is a commentary on traditional art,” he reveals. “I try to destroy the idea of producing artwork or painting on canvas. I don’t want to limit myself. If I keep on repeating myself, I lose inspiration and get lazy. Instead, I challenge the typical and the visual.”

Sometimes, the Muse can come in a very destructive and unexpected way. A lot of Lindslee’s works became casualties of the Super-typhoon Ondoy which flooded his house in Cainta. Picking through the rubble and trying to fix his paintings and his sculptures, the artist was almost tempted to quit. Yet through the ordeal, an idea hit him. “I had wanted to redo everything, but the damage had been done,” he says. “Instead, I looked at what had been destroyed and studied if I could make something new out of it.”

He still takes one day and one exhibit at a time, saying he is living his dream right now. One thing that he is certain about is that he refuses to let conventional standards put his art in a box. “I don’t want to put labels on my work, so that the audience can be free to interpret it,” Lindslee sums up his own personal and artistic vision. “I don’t know how to title or describe myself. I just use my creativity to do what I want. Then if a tragic event like Ondoy happens, I just think positive and stay optimistic about it.”

Photographs by Anna Rafanan, courtesy of Galleria Duemila

Follow Lindslee’s journey as an artist and as a business person on Asian Dragon Magazine’s June – July 2017 issue, available for download on Magzter.